Foreign and Domestic Interaction in the Early Modern Printmaking Network

I presented the following poster at the Sixteenth Century Society Conference in New Orleans on October 18th, 2014. My participation in this conference was generously supported by a travel subvention granted by Iter.

Poster text

Research Questions

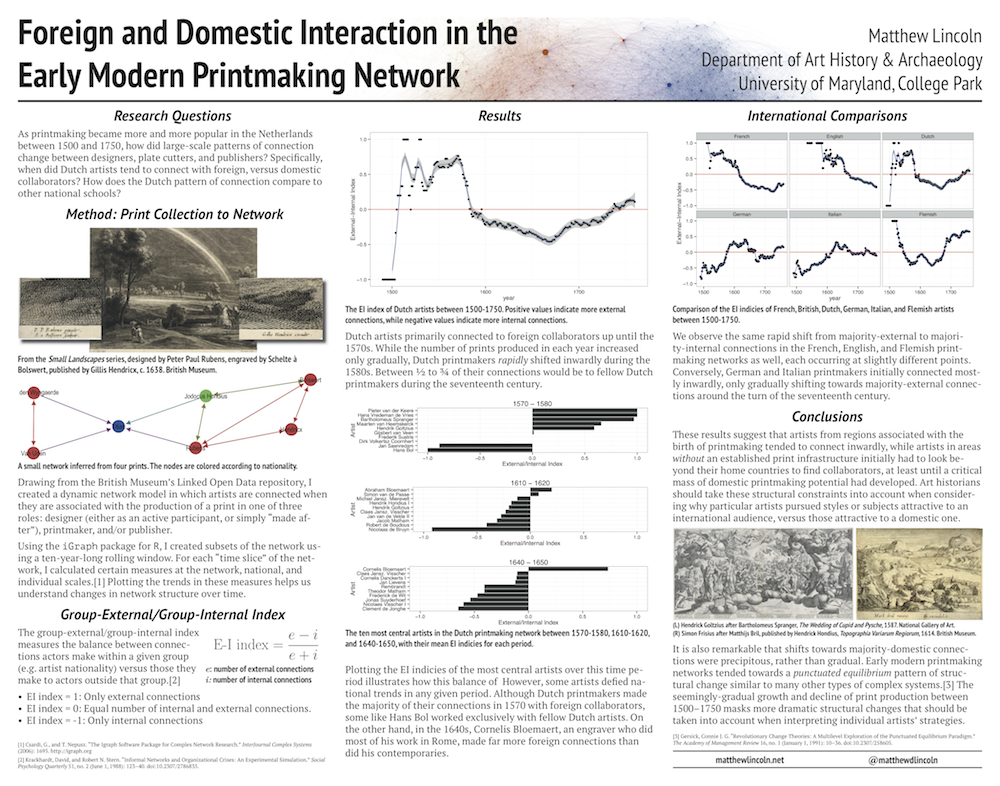

As printmaking became more and more popular in the Netherlands between 1500 and 1750, how did large-scale patterns of connection change between designers, plate cutters, and publishers? Specifically, when did Dutch artists tend to connect with foreign, versus domestic collaborators? How does the Dutch pattern of connection compare to other national schools?

Method: Print Collection to Network

Drawing from the British Museum’s Linked Open Data repository, I created a dynamic network model in which artists are connected when they are associated with the production of a print in one of three roles: designer (either as an active participant, or simply “made after”), printmaker, and/or publisher. Using the iGraph package for R, I created subsets of the network using a ten-year-long rolling window. For each “time slice” of the network, I calculated certain measures at the network, national, and individual scales.1 Plotting the trends in these measures helps us understand changes in network structure over time.

Group-External/Group-Internal Index

The group-external/group-internal index measures the balance between connections actors make within a given group (e.g. artist nationality) versus those they make to actors outside that group.2

- EI index = 1: Only external connections

- EI index = 0: Equal number of internal and external connections.

- EI index = -1: Only internal connections

Results

Dutch artists primarily connected to foreign collaborators up until the 1570s. While the number of prints produced in each year increased only gradually, Dutch printmakers rapidly shifted inwardly during the 1580s. Between ½ to ¾ of their connections would be to fellow Dutch printmakers during the seventeenth century. Plotting the EI indicies of the most central artists over this time period illustrates how this balance shifted. However, some artists defied national trends in any given period. Although Dutch printmakers made the majority of their connections in 1570 with foreign collaborators, some like Hans Bol worked exclusively with fellow Dutch artists. On the other hand, in the 1640s, Cornelis Bloemaert, an engraver who did most of his work in Rome, made far more foreign connections than did his contemporaries.

International Comparisons

We observe the same rapid shift from majority-external to majority-internal connections in the French, English, and Flemish printmaking networks as well, each occurring at slightly different points. Conversely, German and Italian printmakers initially connected mostly inwardly, only gradually shifting towards majority-external connections around the turn of the seventeenth century.

Conclusions

These results suggest that artists from regions associated with the birth of printmaking tended to connect inwardly, while artists in areas without an established print infrastructure initially had to look beyond their home countries to find collaborators, at least until a critical mass of domestic printmaking potential had developed. Art historians should take these structural constraints into account when considering why particular artists pursued styles or subjects attractive to an international audience, versus those attractive to a domestic one.

It is also remarkable that shifts towards majority-domestic connections were precipitous, rather than gradual. Early modern printmaking networks tended towards a punctuated equilibrium pattern of structural change similar to many other types of complex systems.3 The seemingly-gradual growth and decline of print production between 1500–1750 masks more dramatic structural changes that should be taken into account when interpreting individual artists’ strategies.

-

Csardi, G., and T. Nepusz. “The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research.” InterJournal Complex Systems (2006): 1695. http://igraph.org ↩

-

Krackhardt, David, and Robert N. Stern. “Informal Networks and Organizational Crises: An Experimental Simulation.” Social Psychology Quarterly 51, no. 2 (June 1, 1988): 123–40. doi:10.2307/2786835. ↩

-

Gersick, Connie J. G. “Revolutionary Change Theories: A Multilevel Exploration of the Punctuated Equilibrium Paradigm.” The Academy of Management Review 16, no. 1 (January 1, 1991): 10–36. doi:10.2307/258605. ↩