Designing for preservation: static sites and the Digital Humanities Literacy Guidebook

We here at CMU are huge fans of static sites for many reasons. By creating websites that build as a bunch of flat files, it’s very simple to put the end result on a vanilla webserver and not have to worry about maintaining and updating a database service, a web app service, a messaging pipeline, etc.

They can often be a very good match for a digital humanities project if that project’s output is a catalogue-like thing: a collection of content, perhaps with some repeatable types, where the authors need a few good pre-defined templates, and the content pipeline just needs to be them uploading and editing simple files or datasets that can be straightforwardly transformed into webpages. Once transformed and put online, even if the entire project and technical team got hit by a bus, the webpages will still basically work without much intervention needed. Because the files are version controlled, it is also possible to add and edit content in the future

For that reason, we try to funnel many of our projects with a web-based deliverable into a static site solution, including our Shakespeare VR project, the NGA Visual Neighbors project, and the Digital Humanities Literacy Guidebook.

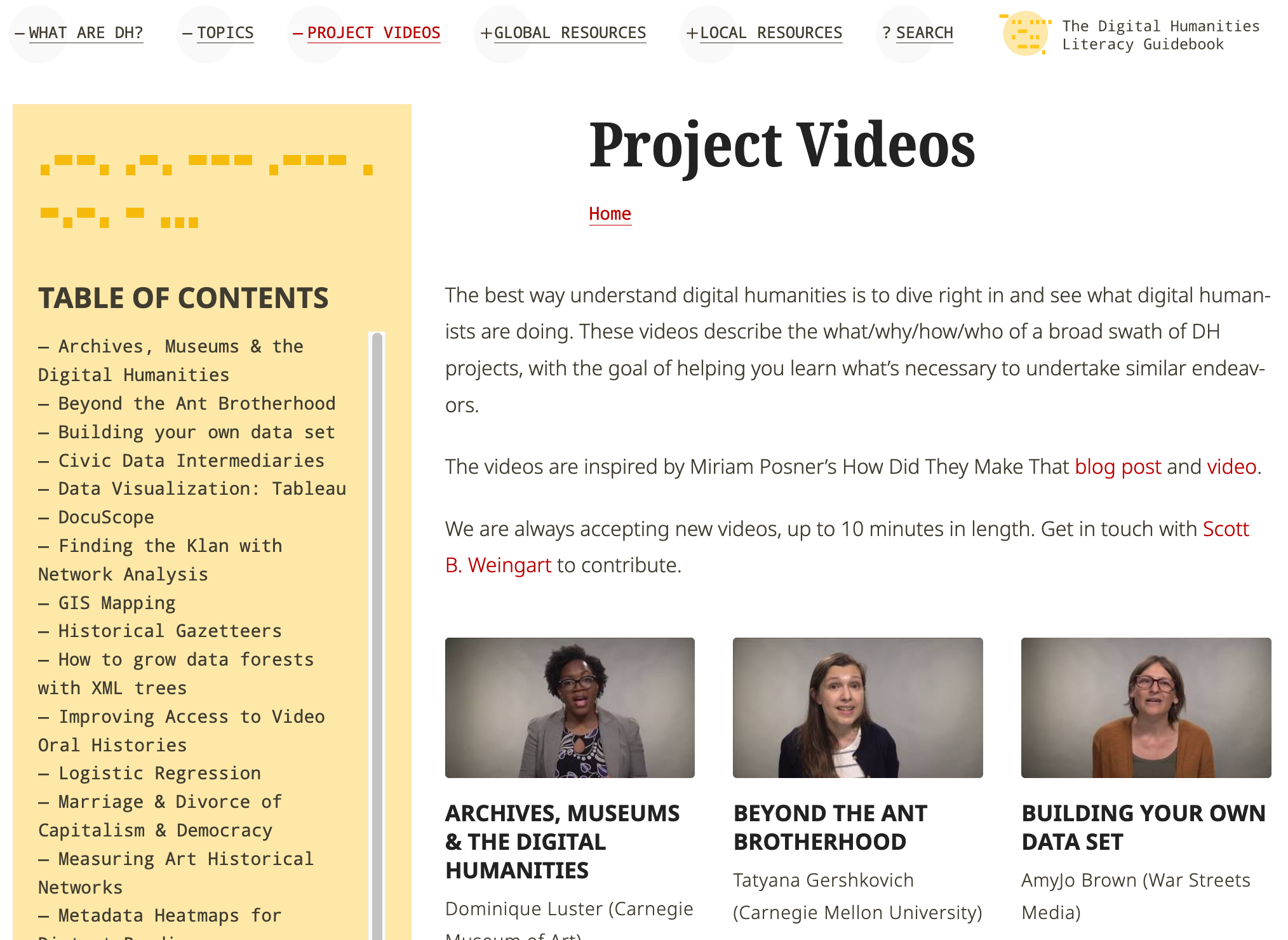

The project videos page of the Digital Humanities Literacy Guidebook

The DHLG, as we like to call it, is one of the key outputs of the A.W. Mellon grant to CMU to kickstart the digital humanities here. It’s a summation of many of the resources and research that is taught at the summer DH workshops. To quote from Scott Weingart’s description of it:

The DHLG is your slim guidebook into this world, like the tourist map they give you when you check in at a hotel. Use it to get your bearings, plot your course, and find the resources that will help you explore further.

Although we had most of the technical expertise to do this project in-house, we (well, I) just didn’t have the full amount of time needed to engineer it all myself alongside our other active projects. That’s why we contracted with Agile Humanities, a DH development shop based out of Toronto, to help drive both the site architecture as well as the visual design and implementation of the project. Learning to work with outside contractors was something I knew this job would entail, given that it’s basically a 1-developer shop here. While we contracted with the excellent Patrick Fulton here in Pittsburgh to implement the design of ETHOS, this was the first project I’d worked on where the external partners were handling essentially the entire stack, with I and Scott managing and assessing the work.

There were two core challenges from an administrative perspective:

- How to figure out a shared language. Both the CMU and AH parties were highly technically proficient, a more symmetrical partnership than some kinds of expert-client relationships. But while we both knew quite a lot about the inner workings of Jekyll, we came to the table with different terms for things like data modeling, defining content types, and so forth. So it took us some time together before we were comfortably speaking each others’ language, and able to answer the questions the other party was asking.

- Timing. Timing. Timing! How to ensure that the internal and external teams have a synced up working schedule, and neither of us is stuck waiting for days for the other to fix a bug or produce some content? This is a huge challenge for us in our internal CMU projects as well (as I discussed in my ACH 2019 talk). I really admired the clear roadmap that Agile drew up at the start of the project, which served us well for the high level view of how the work would progress. Figuring out more low-level details though (how many more rounds of review do we have? What’s the deadline for getting issues in this week?) was a more ongoing process, and one I’ll keep in mind for future projects where we work with external contractors or teams.

Once we made it through these challenges, though, we got a beautiful and functional site (thanks in particular to the inventive design by Bill Kennedy.) And because we have clear git version control, we’re even able to allow external contributions or edit-a-thons (hopefully coming soon!) to add and update the extensive library of content.