Assembling a Monster: The Frankenstein Variorum

Elisa Beshero-Bondar, Raffaele Viglianti, Rikk Mulligan, Jon Klancher, Scott Weingart, John Quirk, Steven Gotzler, Avery Wiscomb, and myself all contributed to a sprawling experiment in the digital collation and publication of a variorum edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

This was a challenging project because it tried to do several new things at the same time.

(The following is a very high-level gloss of the full process that skips over lots of detail - if you want to get into the nitty-gritty details, definitely take a look at Elisa, Raff, and Rikk’s presentation from DH2019)

First, the team needed a way to express collated groups of text across different witnesses in a data structure that was amenable to TEI, and that could do this while pointing out to other TEI documents, not just materializing the entire variorum edition in one file. To do this, Elisa and Raff spearheaded a new genre of standoff TEI - a “spine” - that collects together collated pointers between multiple TEI files representing different witnesses of the same textual location. For example, this bit of TEI:

<app xml:id="C07a_app23" n="16">

<rdgGrp xmlns:cx="http://interedition.eu/collatex/ns/1.0"

xml:id="C07a_app23_rg1">

<rdg wit="#f1818">

<ptr target="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/PghFrankenstein/fv-data/master/variorum-chunks/f1818_C07.xml#C07a_app23-f1818"/>

</rdg>

<rdg wit="#f1823">

<ptr target="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/PghFrankenstein/fv-data/master/variorum-chunks/f1823_C07.xml#C07a_app23-f1823"/>

</rdg>

<rdg wit="#fThomas">

<ptr target="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/PghFrankenstein/fv-data/master/variorum-chunks/fThomas_C07.xml#C07a_app23-fThomas"/>

</rdg>

</rdgGrp>

<rdgGrp xmlns:cx="http://interedition.eu/collatex/ns/1.0"

xml:id="C07a_app23_rg2">

<rdg wit="#f1831">

<ptr target="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/PghFrankenstein/fv-data/master/variorum-chunks/f1831_C07.xml#C07a_app23-f1831"/>

</rdg>

</rdgGrp>

</app>

indicates portions of the 1818, 1823, and “Thomas” editions of Frankenstein. If I were to follow (or “dereference”) those URLs, I’d get back the text at those files:

<app xml:id="C07a_app23">

<rdgGrp xml:id="C07a_app23_rg1">

<rdg wit="f1818">and endeavour to persuade </rdg>

<rdg wit="f1823">and endeavour to persuade </rdg>

<rdg wit="fThomas">and endeavour to persuade </rdg>

</rdgGrp>

<rdgGrp xml:id="C07a_app23_rg2">

<rdg wit="f1831">with the hope of persuading </rdg>

</rdgGrp>

</app>

This structure explicitly demarcates a change history structure of the novel in a way that we can compute over, flipping from edition to edition even as Shelley moves, adds, or deletes entire paragraphs or chapters.

We can only get to this “spine” once the actual collation work itself has been done. Although their are algorithmic aids for collating variants of a text, it is still involves an enormous amount of human attention and adjustment. Elisa bravely spearheaded this task, in which she iteratively used the aid of CollateX alongside close manual reading, a human-computer loop that gradually refined collated “chunks” from the first sections of the novel, up through chapter 4.

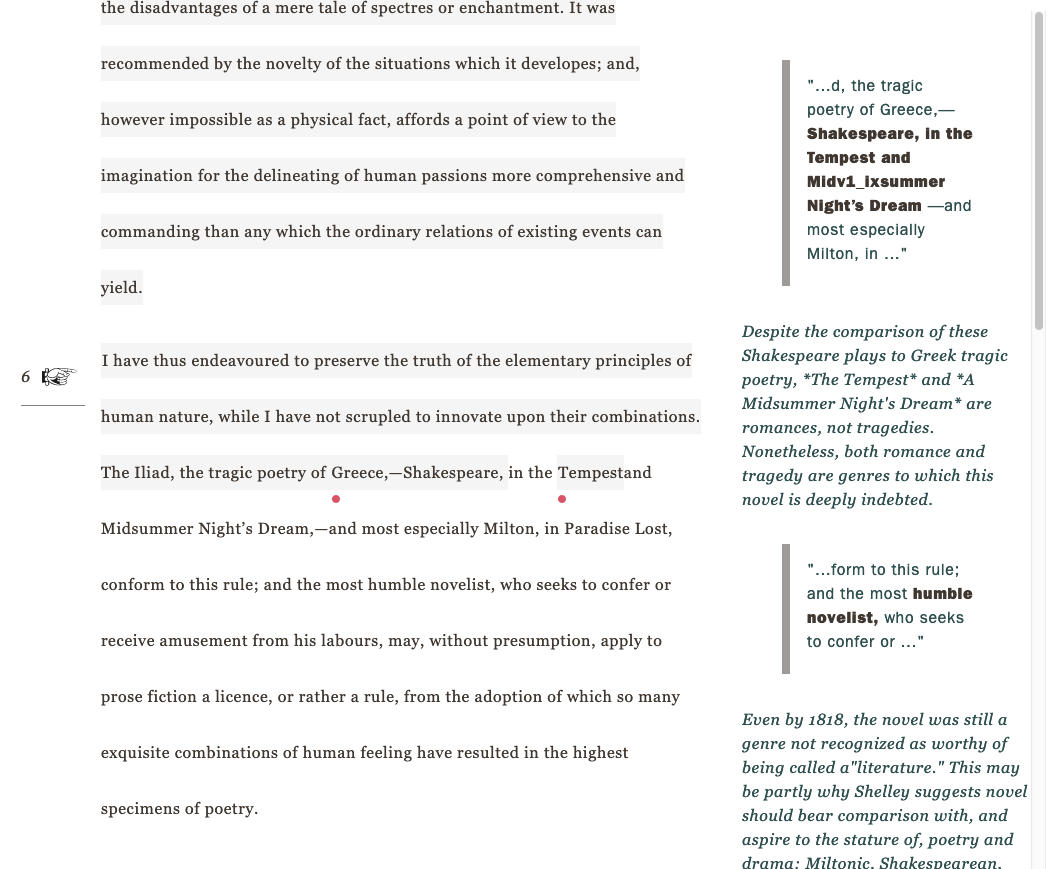

Next, this TEI is all well and good for machines to read, but we need to render it in some way to make it easier for human readers to navigate. This is where innovative work by Raff and the Agile Humanities Agency on rendering TEI docs into your browser via javascript (rather than using XSLT to create an entirely separate static HTML file) comes in to play. The result is The Frankenstein Variorum prototype viewer.

A screenshot of the prototype Frankenstein Variorum viewer.

“Why go through all this bother?” you might ask? By doing this rendering live in the browser with JavaScript (using the CTEIcean library), it lets us point to TEI files in any old location - they don’t all have to live within our website under our control, and we don’t need to watch those TEI files for changes in order to regenerate our HTML representation of them. Case in point: if you visit our prototype viewer, you’ll have an option to view 5 different witnesses of the novel’s text. The manuscript version (or “MS”) doesn’t live on our site at all. Its TEI lives in the Shelley-Godwin Archive. If they updated or corrected their TEI, the updated text would appear on our viewer immediately. Likewise, as Elisa’s collation of the different editions progresses, the new collations will immediately be live in the online viewer.

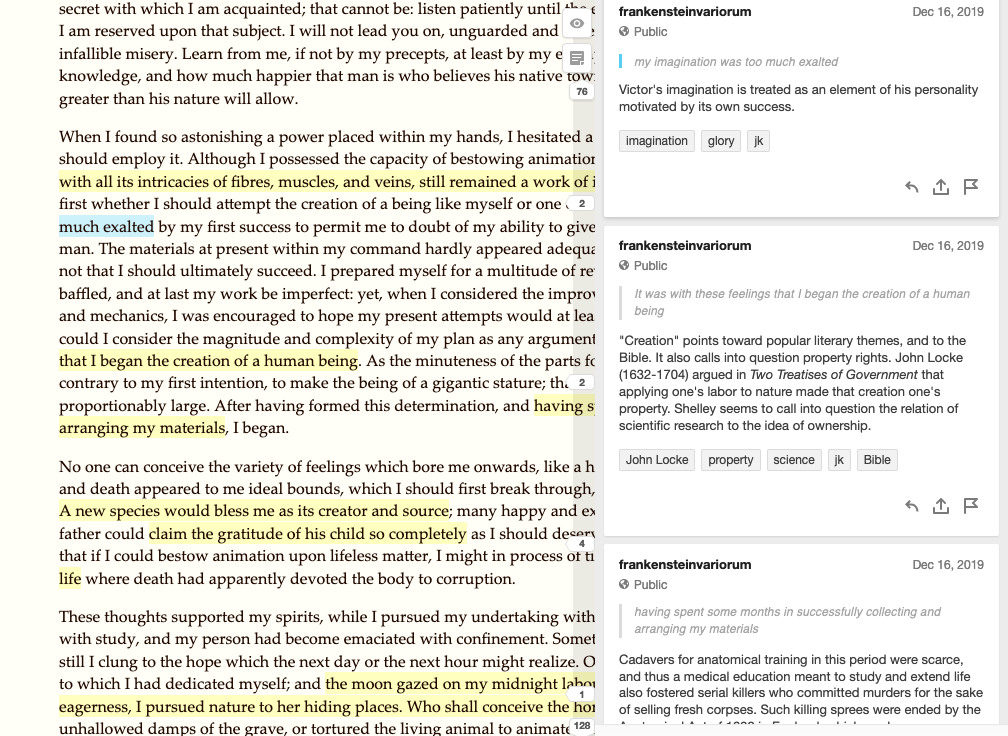

So far so good for collating these editions. But our project also featured a second team, headed by Jon Klancher of CMU English with graduate students Avery Wiscomb, John Quirk, and Steven Gotzler, that was busy producing scholarly annotations on these editions, discussing the significance of Shelley’s modifications to the novel. “Uh oh,” the experienced project manager might say, “isn’t that work going to depend on having all those collations totally finished ahead of time? And aren’t you now ALSO responsible for figuring out some kind of annotating interface for that team?” To avoid these blocking dependencies, the annotations team worked from already-prepped HTML versions of the different Frankenstein editions, and used the open-source Hypothes.is annotation environment to collaboratively mark up the texts (see, for example, the 1818 edition).

A screenshot of the hypothes.is annotation interface on the 1818 HTML edition of the novel.

Using the Hypothes.is API, we could harvest these annotations as JSON and integrate them into our prototype viewer. This also let our annotations team work on whatever part of the novel they wanted to, rather than needing to wait for the paintstaking work of collation to be complete. This means that while our prototype viewer shows only those annotations that overlap with the completed collation work, you can see all of the team’s annotations within the single-witness pages.

All together, this project did an enormous amount. However, you’ll see it is still very much a prototype, a proof-of-concept with all the unfinished business that comes with it. Yet because we worked out a project plan that allowed for components to be only partially finished and to have intermediate milestones, we’re still able to deliver a very interesting prototype, as well as real usable data after this first phase of the project.