American Art History and Digital Scholarship: New Avenues of Exploration

These are some live notes from the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art symposium “American Art History and Digital Scholarship: New Avenues of Exploration” on Friday November 15, 2013.

Diane Zorich has also created a great Storify page of the very active #AAHDS twitter feed.

(Edit 2014-02-06): Diane has also now published her formal report (PDF) on the symposium.

I’ve arranged it by session and paper, with a final section of random thoughts. Please comment if you’ve anything to add from the sessions!

Table of Contents

Mapping Images

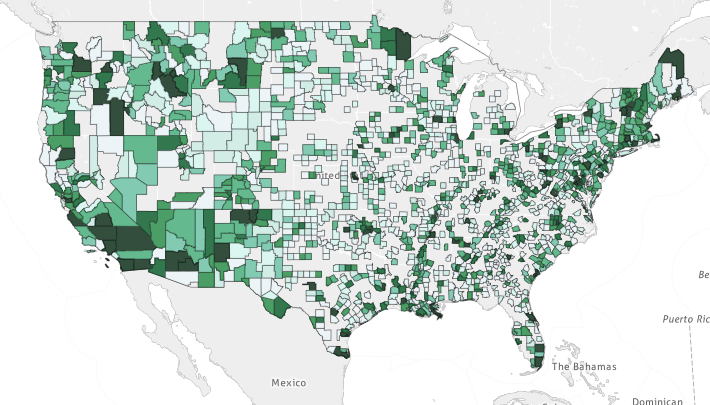

Photogrammar

Laura Wexler and Lauren Tilton presented their Photogrammar project that maps the locations of thousands of photographs taken during the Great Depression by the Farm Security Administration. Though the conventional wisdom is that FSA photos focused on the south and the dustbowl region, a national map of the actual photograph locations immediately challenged this assumption, presenting quite a different, diversified picture of where photographs were taken. In Wexler’s thoughtful words, the FSA project was not a document, but a simulacrum of the U.S. – a representation without an “authentic” original.

Particularly exciting was when Laura Tilton started giving us a tour thought the map. By visualizing the locations of each photograph, she made it clear you could closely track individual photographers as they moved across the country. Also interesting was confronting the legacy classification tag system that comes with these photos. Intriguingly, different shots of the same scene could be sorted into completely different categories: a portrait-like image of a man is tagged “People as Such – Middle-aged man”, but an image of the very same person playing the piano becomes “Entertainment” – how telling that formal, compositional changes can change completely our perception of the content of those images.

Schematizing Landscape with the Inventory of American Paintings

David Sledge (Williams College represent!) wanted to see how he could use new tools and techniques to better contextualize images of American landscapes. He used the Inventory of American Paintings compiled by the Smithsonian as a massive database of American landscape painting writ large.

Sledge was particularly interested in understanding what locations American artists depicted. By mining the metadata of the IAP, he could draw out interesting trends in the numbers of artists painting particular subjects at any one time, with results that served as an invitation to new research. For example, if New York was the most-painted city in American landscapes, why was Venice, Italy the second-most-painted? And if this surprises us (as it seemed to do for many in the auditorium), what does this say about lacunae in American art scholarship and about the assumptions that scholars have made about the grand narratives of American landscape painting? He ended with a call for museums to release their databases not just in web forms designed for single-record lookup, but in raw forms that allow utterly different kinds of processing.

Computational Analysis of Andy Warhol’s Flowers

Marian Mazzone and Thomas Brady tried to apply computer image processing techniques in order to look at Andy Warhol. For an art historian not interested in attribution questions or in differentiating style (as Mazzone said tartly, “I don’t need a computer to do that for me, I can use my eyes”), what can computer vision give to us? She turned to Warhol’s flower series in part because there was a large body of materials (paintings as well as prints) to process, and since the images are based off of a single photograph, the differences between images can be more easily schematized and abstracted.

Since computers are not (yet) useful for classifying “style”, Marian decided to simplify and ask basic schematic visual questions like “color”. She wondered if we could detect patterns of changing artistic choices (e.g. color, rotation, scale) over a long series of works? Thomas Brady, a computer science undergraduate who partnered with her on this project, discussed how they got the computer to quickly record the flower colors of all the series images. Using this information, they were able to start counting up images with certain characteristics (flower size, flower color.) Though Mazzone and Brady didn’t share conclusions from these data today, they hope to combine this information with a network analysis of the movement of these images between galleries and collectors to see if any correlation can be found between formal properties and the exchange and distribution of these artworks.

Networks and Contexts

Visualizing Schneemann

Michelle Moravec discussed Carolee Schneemann through the lens of of the Schneemann correspondence digitized by the Getty. Through a blizzard of visualizations (perhaps too many too fast?) [ed: wonderfully, she’s shared her slides here] Moravec explored the balance of male to female correspondents of Schneeman, derived from Named Entity Recognition algorithms. She also wanted to see Schneemann’s use of the past – literally, the word “past” – in her correspondence.

Melissa Rogers (UMD what what!) was curious about Schneemann’s “mail art” and its interaction with her other performances, films, and assemblages. She wanted to see if she could map out the mail art geographically. She laid out her project for mapping Schneemann, and walked through the questions that she as a graduate student must confront when embarking on this kind of digital project. A good part of her talk was actually discussing her own trials and travails working with Omeka and Neatline to do so. Talking with Rogers later, she emphasized how she wishes more digital humanities developers would interrogate the assumptions they build their tools on.

Documenting the Postwar Audience for American Avant-Garde Art

When introducing her approach to researching American avant-garde art, Titia Hulst invoked the work of John Michael Montias, an economic historian who looked at the seventeenth-century Dutch art market on a large scale. Through Montias, Hulst called for art historians not to neglect (in so many words) the forest by looking too closely (and thus privileging) individual trees. Her project traverses and attempts to re-map the (rather rocky) territory of the history of exhibitions of American avant-garde art. She discovered that her initial subject – the gallerist Leo Castelli – was quite the unreliable source, whose own claims and writings have distorted the literature on this market history.

In order to evaluate these claims, Hulst says she had to become an “accidental” digital historian through using AAA-digitized invoices. She created her own table of more than 20,000 transactions from these and other files. Interestingly, she compared the trends in her data to historic GDP trends, in order to discern trends in taste for particular artists (not just the overall trend in art buying writ large.) From this, she was able to compare the character of galleries collections (diversification of artists held) as well as their market share across US cities.

Hulst also mapped the locations of purchasers from different gallerists. The results run counter to Castelli’s own story – that he was promoting avant-garde art in places no one else did. Rather, it seems he didn’t sell anywhere other gallerists weren’t already selling.

She wanted to grapple with the question of “taste” – not style, embedded in the artwork, but the reasons why collectors wanted certain artworks. Categorizing by these categories of “taste” (e.g. “cool” abstraction, “expressive” abstraction, “fantasy”, etc.), it seems Castelli sold far more figurative work than he claims in his own narratives.

Finally, and most interestingly, she used network analysis to see which collectors bought from multiple gallerists – early on, it was only museums doing this. Moreover, Castelli had a tighter network than anyone else, suggesting his own very different practice from other gallerists.

The Warhol Timeweb

Jessica Gogan and Tresa Varner from the Any Warhol Museum presented their Timeweb platform for exploring the cultural context of Warhol’s artworks, which I think is better seen than read about, so go visit it! I did particularly like that they considered museum technology from an education standpoint – the Warhol museum wants to make sure it uses tech to the utmost, but that it gives visitors a “break” from the technology and its noise when they are looking at the art itself.

Curating Online

Student Curators Online

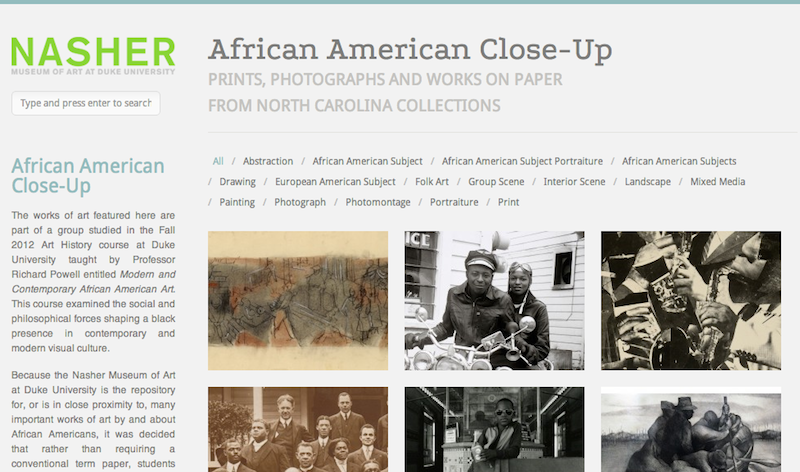

Richard Powell hates reading papers.

Or rather, he clarifies, he is disappointed at seeing in an increasing number of undergraduate papers only a reflection of students’ skill at pulling information from the internet, telling him little else about anything. So he has endeavored in his course on African American art to see how he could engage digital technology to reverse this trend. Working with the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, he identified a group of objects (within a driveable radius of campus to make sure students would be able to see these works face-to-face) in order to create a digital exhibition written by his students.1

Powell presented this material to his students as a research assignment. Their work was to identify objects that they would be interested in looking at and researching in depth. But they were not just to write about these works. They were to follow a process of formal analysis, external research, and articulating their own personal, subjective reaction to this work – to add their own genuine content to our thinking about these works.

The students were then supposed to compress that into just 500 words for their contribution to this website – in other words, a catalog entry! And this entry would not just be critiqued by the professor, but would be workshopped by the class as a whole. Powell asked the students not only to think about their texts, but also to grapple with the challenges of abstracting their work into “categories” and “tags” which would sort and define the paths of visitors to the online exhibition. The results, he found, were far more invigorating essays than he’d ever have expected from these students, not to mention a fantastic online resource now shared with the public at large.

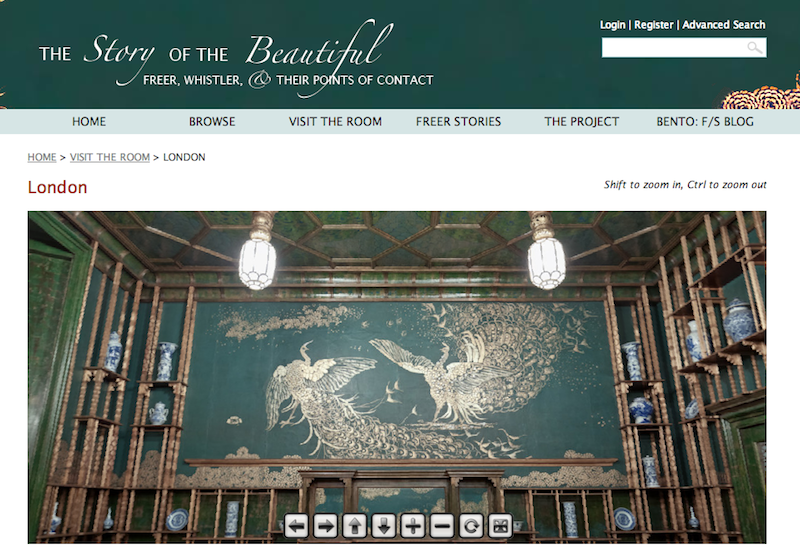

The Peacock Room

The Freer Gallery of Art has created a fantastic digital archive on Charles Lang Freer’s Peacock Room in cooperation with Wayne State University. This site tries to unify a virtual tour of the room and its objects with the historical context of the space constructed through photographs and archival documents.

The online version of this space offers several benefits unique to the digital environment. Lee Glazer says they have analyzed user statistics on this website and found a huge number of international visitors who now have a chance to see this room without having to travel to the real spaces. The virtual version of this room also makes the space more dynamic than possible in real life – they can show the two different versions of this room: as it was in London, and as it was in Detroit. Their site also chronicles Freer’s world journeys to understand wehre these Peacock Room objects came from. Finally, users can add their own comments and tags to these works – they report a German scholar alerting them to a dating error on one of their ceramic objects, which allowed them to make a correction in their own catalog system in the Smithsonian.

The Peacock Room site has also been developed as an iOS app with zoomable, interactive panoramas of the peacock room. In a departure from the Warhol Museum, the Freer and Sackler want people to engage with their technology while in front of the objects. By doing so, they argue, they can allow visitors to “dive deep” into the collection information without having to clutter the room with labels or stationary computer kiosks to the detriment of the overall aesthetic experience of the space – one of Freer’s original priorities. (I’m glad to note that iPads are also loaned out for free to visitors who don’t have their own!)

Glazer closed with a reflection on the iterative nature of these apps, quite unlike the one-and-done exhibition project. She also raised the dangers of an overly-slick app that gives a directed, simplified presentation of the room – a sleek, commercial application rather than an academic website.

Publishing Online

Searching for Siqueiros

Joan Saab discussed the evolution of the platform Scalar, a free open-source platform that allows authors to write born-digital (and non-linear) scholarship online.

Her own project followed the dissemination of the mural imagery of David Alfaro Siqueiros, a project she has come to call Searching for Siqueiros. One of the exciting challenges of this project was the multimedia nature of Siqueiros reception – not just books and articles, but film, posters, blogs, even Facebook pages. Rather than trying to force her project into a linear narrative, she decided to instead “explode it” in Scalar, allowing the many threads of the Siqueiros story to interweave in a multi-layered visual argument.

She described the properties resulting project (you can read up on the platform tools on the Scalar website). One characteristic of the Scalar platform is that you can “tag” your pages, and then visualize these tags. By using these tags, Saab, found connections and themes in her own writing she may never have noticed otherwise. Visualizing the organically-expanding narrative flows caused Saab to reflect on her own process of research and writing.

Digital Projects in American Landscape Design History

Therese O’Malley from CASVA described two different publication projects.

The first, Keywords in American Landscape Design was a 10 lb. paper publication cataloging landscape designs through 100 different keywords, each of which was accompanied by a short essay and then a host of examples and scholarly citations. They are now working on a digital relational database that will easily surpass even a 10 lb. printed book. They are expanding the Keywords project using the MediaWiki platform. This allows a highly flexible mix of linked text, keywords, locations, and people, all connected to images and as many citations as you could possibly want, unconstrained by the limitations of physical print. They manage their bibliography through a shared Zotero library that users can access and download separately. Because this project has been built on a wiki, it is easy to maintain and it can be published iteratively without waiting for it to be “complete”.

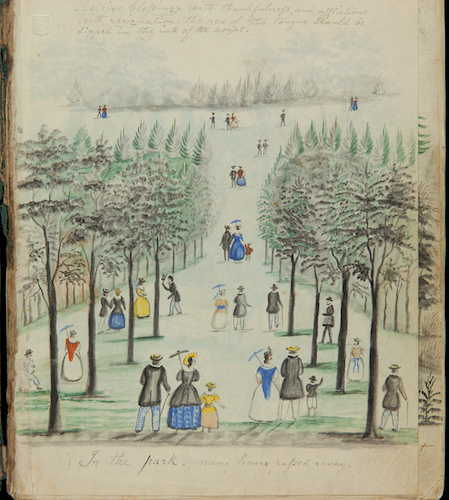

The second project is a digital edition of a small watercolor landscape sketch album by Lewis Miller, an American folk artist. Miller, O’Malley noted, has often been used as a way to illustrate folk life, while the artist himself has not been rightfully considered in his own right. Their work (a multimedia project published in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide) involved creating an annotated digital edition of this text. Doing so allowed them to explore the full popular culture context of Miller’s drawings, unveiling him as a person who participated deeply in contemporary cultural life. This linking allows the authors to bring so much more evidence to bear on their theories than they could do in a conventionally-published project.

Art History Online

Emily Pugh (also of CASVA), discussed the digital research and publishing initiative that is Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, an open-access, online, peer-reviewed publication supported by the Mellon Foundation. While not seeking to change the format of the journal as a whole, they decided they wanted to devote at least one article per issue to scholarship whose generation and presentation involved digital tools. You can see their standing CFP for digital art history projects here.

She gave us some insight into her discussions with authors about their technological and research methodology, and how during the research phase they try to anticipate the challenges and opportunities of the online publication phase. Some of her ongoing challenges included revising traditional scholarship workflows given the chicken/egg question of content and format when it comes to digital scholarly publishing. Happily, with each project grappling with different types of digital content, the journal gains more experience that it can share with researchers to help streamline the project. The journal also felt a responsibility to help conceptualize key methodological questions for digital art history:

- When is something published? When it is added to the journal? Whenever the author updates the original map in the future?

- How does the user interact with publications? What need is there for fixed content as part of an ongoing dynamic project?

- Who owns the content? What if an institution owns a database? What if a university gives resources to an author to help them develop a digital resource – can the journal just co-op that product?

- Workflow, workflow, workflow: what does an editor need to know about the specifics of publishing a digital journal, the steps involved and the skills (i.e. human resources) that must be marshaled? What about peer review – art history versus/plus digital humanities experts?

Random bits

- I’ll note they have a very neat idea to have people sign up on large categorical posters (“Digital Pedagogy”, “Data Mining” etc.) as a way to find lunch partners, and also as a way to kick off a prolonged digital conversation.

- The organizer Kelly Quinn was incredibly conscientious to ask for clarification whenever anyone name-dropped a technology, and cleverly typed up the names of tools onto an open PowerPoint slide so people knew how to spell them!

- Kelly also raised a question near and dear to my own heart: how current graduate students in art history who are interested in pursuing digital approaches to research should try to mold their education and graduate experiences. There weren’t too many answers forthcoming.

-

This project is based on WordPress, and uses the “Infinity” theme which allows you to integrate a mini-slideshow of high-resolution photos into your posts. ↩