Unsustainable Museum Data

“How can we ensure our [insert big digital project title here] is sustainable?” So goes the cry from many a nascent digital humanities project, and rightly so! We should be glad that many new ventures are starting out by asking this question, rather than waiting until the last minute to come up with a sustainability plan. But Adam Crymble asks whether an emphasis on web-based digital projects instead of producing and sharing static data files is needlessly worsening our sustainability problem. Rather than allowing users to download the underlying data files (a passel of data tables, or marked-up text files, or even serialized linked data), these web projects mediate those data with user interfaces and guided searching, essentially making the data accessible to the casual user. But serving data piecemeal to users has its drawbacks, notes Crymble. If and when the web server goes down, access to the data disappears:

When something does go wrong we quickly realise it wasn’t the website we needed. It was the data, or it was the functionality. The online element, which we so often see as an asset, has become a liability.

Some of the most ambitious digital humanities projects that have taken a very deliberate approach to standardizing and structuring their data, like the Map of Early Modern London, offer no way to download their content en masse, instead keeping the user completely reliant upon their web interface.

I am starting to see this as a crucial problem in the world of museum data. We’ve been duly excited about the rapid adoption of APIs by many museums, libraries, and other archives as a way to make their collections data available in a machine-friendly way.1 For example, the Cooper-Hewitt museum has made a splash with its particularly rich and well-integrated API. This format makes excellent sense for generating human-readable websites or mobile apps, which only ever need to display a little information at a time. They’re also great for relaying information that may change frequently, such as the current display location of a work of art.

While APIs are to be lauded, they are still essentially web services, which spit back small segments of a larger database in response to live queries by users. Thus they will fail if a server goes down, software updates introduce incompatibilities, or they are overwhelmed with requests. APIs are also a poor solution for the researcher who would like to analyze the entirety of a collection database. Even when APIs are functioning normally, a researcher interested in downloading the entire database behind that API must spend an inordinate amount of time customizing a script to automate requests, and then hope that nothing breaks in the hours it can take to download everything record by record.

Far easier on the user (and on the web server) is to offer exports of these underlying databases as static files that can be downloaded in bulk and analyzed at will. Moreover, copies of these “flat files” can easily be uploaded to multiple institutional repositories, provided the museum has had the good sense to allow it under their licensing of the data. The British Museum offers an API-like service to query an LOD representation of their collections data. As is commonly a problem with these LOD services, the BM’s web service is often malfunctioning. However, the BM has smartly allowed users to download a dump of their linked data so the information can remain available locally, even when the remote web service is not.

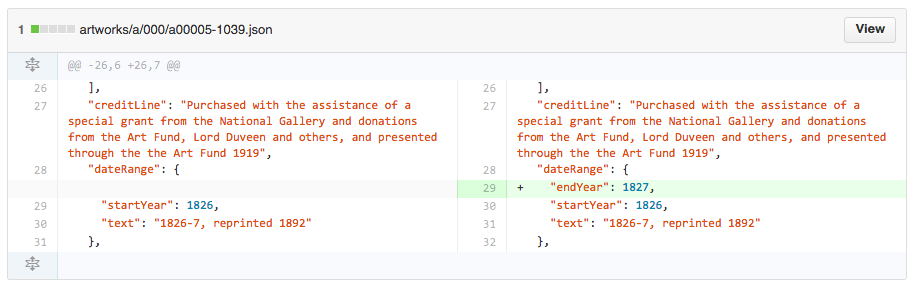

I am also interested to see how many museums will follow the Tate Gallery’s and Cooper-Hewitt’s use of Git as a way to track and distribute structured information about their collections. A Git repository combines the ability to bulk download, while also providing a way to track and distribute changes to a dataset asynchronously, not relying on a constantly-churning web service.2 There is also a ready-made framework for assigning DOIs to git repositories.

I’ll end this post with a call to both the university DH crowd and the #museweb crowd to prod each other to take advantage of this most simple way of distributing their humanities data. To offer these exports seems to be trivial compared to creating web-based user interfaces or APIs, so I suspect that such offerings are rare because project leaders just don’t think to include them (though I’d be interested to hear otherwise!). If the GLAM world is going to spend a lot of time and effort developing good APIs, they might as well embrace the “keep it simple, stupid” principle and simultaneously publish flat dumps of the data they are already releasing via more complicated methods. The same goes for scholarly research projects by university professors. Flat files encourage easy downloading and distribution, not to mention creative re-use, and they are great for sustainability. “Lots of copies keeps stuff safe,” after all.

-

For an introduction to Application Programming Interfaces, see the Programming Historian. ↩

-

Though it’s important to note that particularly large databases, like that of the British Museum, might exceed git’s scaling capability. ↩