Tips for a good hackathon

All work and no play makes a dull developer.

That’s why I was really excited to help pull together a crack team of artists, engineers, and art historians to represent Pittsburgh at the National Gallery of Art’s first ever “datathon” in October.

The NGA wanted us to assemble teams expert in both art history and data to work with a very rich export of their collections metadata, and to publicly present results that were directly relevant to art historical and curatorial questions, and not just finding fun patterns with no scholarly import.

Sarah Reiff Conell, Lingdong Huang, Matthew Lincoln, and Golan Levin at the National Gallery of Art, October 25, 2019

Our team comprised myself, Sarah Reiff Conell (a PhD candidate at the University of Pittsburgh), and Golan Levin and Lingdong Huang from CMU’s STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. You can read more detail about how we calculated nearest visual neighbors using a neural network (this is pretty old hat) but then used that layout as the base of data visualizations to explore collecting history.

Paintings from the NGA and the Kress Collection arranged by visual similarity and colored by original collector.

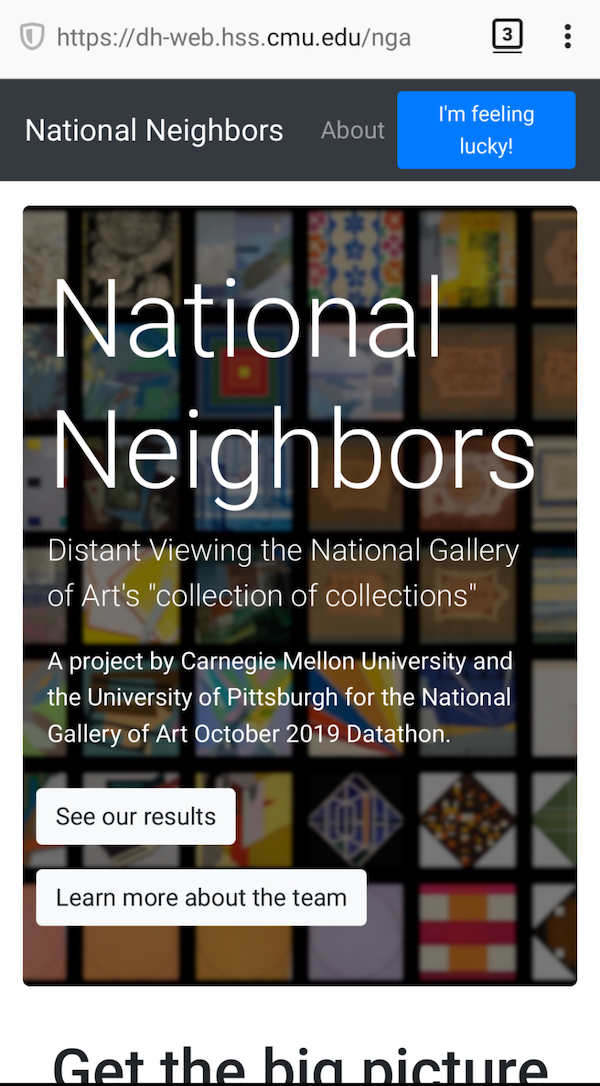

Another fun thing that came out of it was this lil’ web app I built with an “I’m Feeling Lucky” button, that will pull up an NGA work at random1 and display its nearest visual neighbors according to our processing of the data. Please go try it out!

A screenshot from https://dh-web.hss.cmu.edu/nga

It’s a neat way to hopscotch around the collection, and it works nice and smooth on your phone, so lately I’ve been whiling away my wait for the bus home by finding delightful corners of the collection I’d never seen before, and jumping between centuries or media in a way that I wouldn’t be able to do as serendipitously in the flesh. I have a whole separate post to come At Some Point® on how this intervention in collection navigation demonstrates just how broken the idea of “browsability” is when it’s applied at the scale of an entire art museum, yet what a perfect idiom it can be for certain corners within that collection.

But since I’m posing this in the #cmu-dh series, I wanted to reflect here more on the process of the event. As these kinds of events go, I was very pleased with how things panned out. I’ve been to a few cultural data hackathons/datathons over the years, and they’re very difficult to bring to a conclusion that is satisfying both for the hosting institution as well as for the participants. The NGA, and their main organizer, Diana Greenwald, did a lot of things very well here that many datathons miss:

- They proactively formed teams, making sure that we had shared ideas and goals ahead of time. Lighting can sometimes strike at hackathons where people pair up serendipitously and create cool things, but preparation really makes for the best improvisation. We had a chance to pull together ideas and decide on goals before we got there, so all our time could be spent implementing.

- They shared the dataset a full month prior to the event, and my god did they provide documentation. We got PDF dozens of pages long describing each table and field, and one that was clearly put together by people who were used to trying to get real knowledge out of the data, so they were filled with very useful advice on naming conventions and gotchas.

- They provided multiple relational tables, rather than 1) giving us an undocumented API and saying “good luck” or 2) de-normalizing the database into a massively simplified CSV that would have curtailed many of the kinds of operations that we’d want to do. While the simple CSV is a good view to provide for something like an intro workshop or tutorial, they rightly knew that the hackathon teams would each have at least one person capable to do the joins and filters needed to create the view of the data that team needed.

- They actually organized a conference call with each team so we could ask questions! And when we asked for images (which is a fundamentally different problem than giving a CSV dump) they gave frank and informative answers about what they would and wouldn’t be able to give to us.

- Perhaps most importantly, they set very clear expectations about what they wanted us to do. This was to be an art-historically-informed investigation. Not only did they make sure that art historians were on each team, but they also provided an extensive list of example questions from curators and collections managers at the NGA. This is particularly important for museum data, because you just can’t answer questions about the generic history of all art with the data from just one museum. At best, you can answer some often very interesting questions about the history of that museum and how it has grown. This was really useful for shutting down unproductive lines of inquiry and helping us focus in on things that were both do-able and interesting to the hosts, rather than spinning our wheels.

- Not for nothing: they fully paid for travel, accommodations, and food, and made also sure there was a coordinated press push so that we’d all be credited, cited, announced, and live-streamed. With several years of this stuff under my belt, it’s hard to get excited about a hackathon, because it’s a lot of effort for very little product at the end, besides a (usually pretty mediocre) opportunity to network. It was much easier to say “yes” to this because of the clear material and organizational support, and knowing that we’d get very good publicity for our work.

That’s not to say it was a cakewalk!

- Although I had pulled together our team in advance, we did not have the capacity to meet and work at all prior to the event, so we needed to very quickly scope out each others’ abilities and interests once we were on the ground. We’d already put together the general idea of visual similarity across collections, but needed to swiftly figure out what parts of the workflow each person would handle. It didn’t take long for us to determine that I and Sarah would be the ones to wrestle directly with the NGA metadata, passing off only the most important extracts to Golan and Lingdong, who had to spend most of their time actually processing the tens of thousands of images through their neural network, and fine tuning the visualization system they had in place.

- Part of what helped us pick our goal was Golan’s pre-existing work on visualizing large collections by visual similarity. They had a very efficient tool; we just had to bring well-formatted data and some good questions. We did not need to build everything from scratch in 48 hours.

- Well in advance, Sarah had made the brilliant suggestion to bring in images from the Rosenwald Collection and the Kress Collection into our analysis. This let us expand beyond the walls of the NGA, which made it a far more compelling project.

- We figured out two specific questions we wanted to answer, and because of that, our process had very specific outputs: several beautiful visualizations, as well as a large dataset of the extracted features of the images that you can download right now and try your own distance metrics on.

- All this prep, and we were still pressed for time! As Golan were walking from the NGA’s West Building to the East Building where we were due to present our findings to a packed auditorium, we had to make sure to keep our laptops close enough to finish AirDropping finished visualizations.

- The NGA is physically built for, and its outreach programs designed around, formal academic seminars, not unruly hackathons where teams will want lots of WiFi and power and not need to wait for security badges. This was not a debilitating problem, we still got our work done. But I admit, it was amusing for me (who’d worked there during grad school and was accustomed to the many checkpoints and rules and strict hours and mandatory scholarly tea sessions and lack of power outlets) watching the artists from CMU chafe against the unending restrictions put on them, when back at home they have a truly 24/7 studio.