Computer Vision’s Digital Surrogates, and Implications for Collections Management Technology

Last week I had the pleasure to participate in the virtual DH Nord 2020 conference “The Measurement of Images. Computational Approaches in the History and Theory of the Arts”.

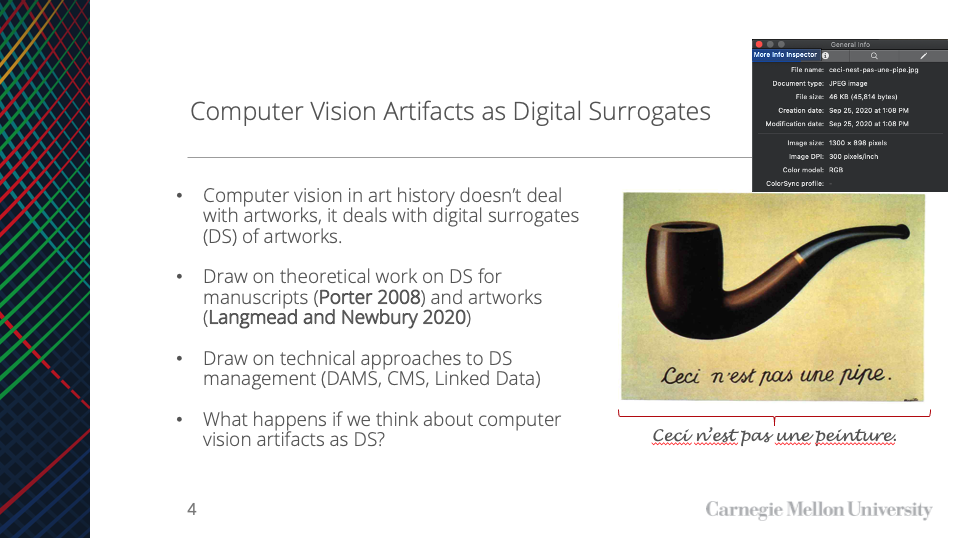

Placed on to a panel with several active computer vision and art history researchers, I felt the need to explicitly articulate my gradual move from art history researcher to a technologist interested in a wide array of cultural heritage data infrastructure problems. I could not realistically offer exciting new computer vision techniques, nor was I invested in a particular art historical question. I instead wanted to bring the perspective of the cultural heritage institution to the roundtable. My main question: what could we gain by thinking of computer vision artifacts like trained model weights or vector representations of individual images as digital surrogates for art objects, not unlike the digital photographs and descriptive metadata that museums maintain of the physical objects in their care?

Watch the talk and the others on the roundtable.

Computer vision artifacts as digital surrogates?

What I would add here (and will hope to articulate further in the final published proceedings, hopefully coming out next year) is that I didn’t intend to literally argue that museums must store image vectors in their current collections management systems (..aha ha, just kidding.. unless..?) Instead, I hoped the lightly-provocative title could compel more conversations amongst collections data managers, computer vision researchers, curators, and academic art historians about using theoretical frameworks for digital surrogates when talking about CV models, especially for use in the art museum context.

Art historians have long discussed the limitations and affordances of surrogates for our artworks, from engraved reproductions to lantern slides to JPEGs put into PowerPoints and projected on to lecture hall screens (or, in 2020 and beyond, squished in to Zoom meeting windows). Physical and digital surrogates for early printed books and manuscripts are also an active site of theorization. I have particularly enjoyed Dot Porter’s framing of the “uncanny valley” of digitized manuscripts for its capacious view of what can constitute a surrogate of one of these objects, and how the presentation frame of a surrogate can make or break its affordances.

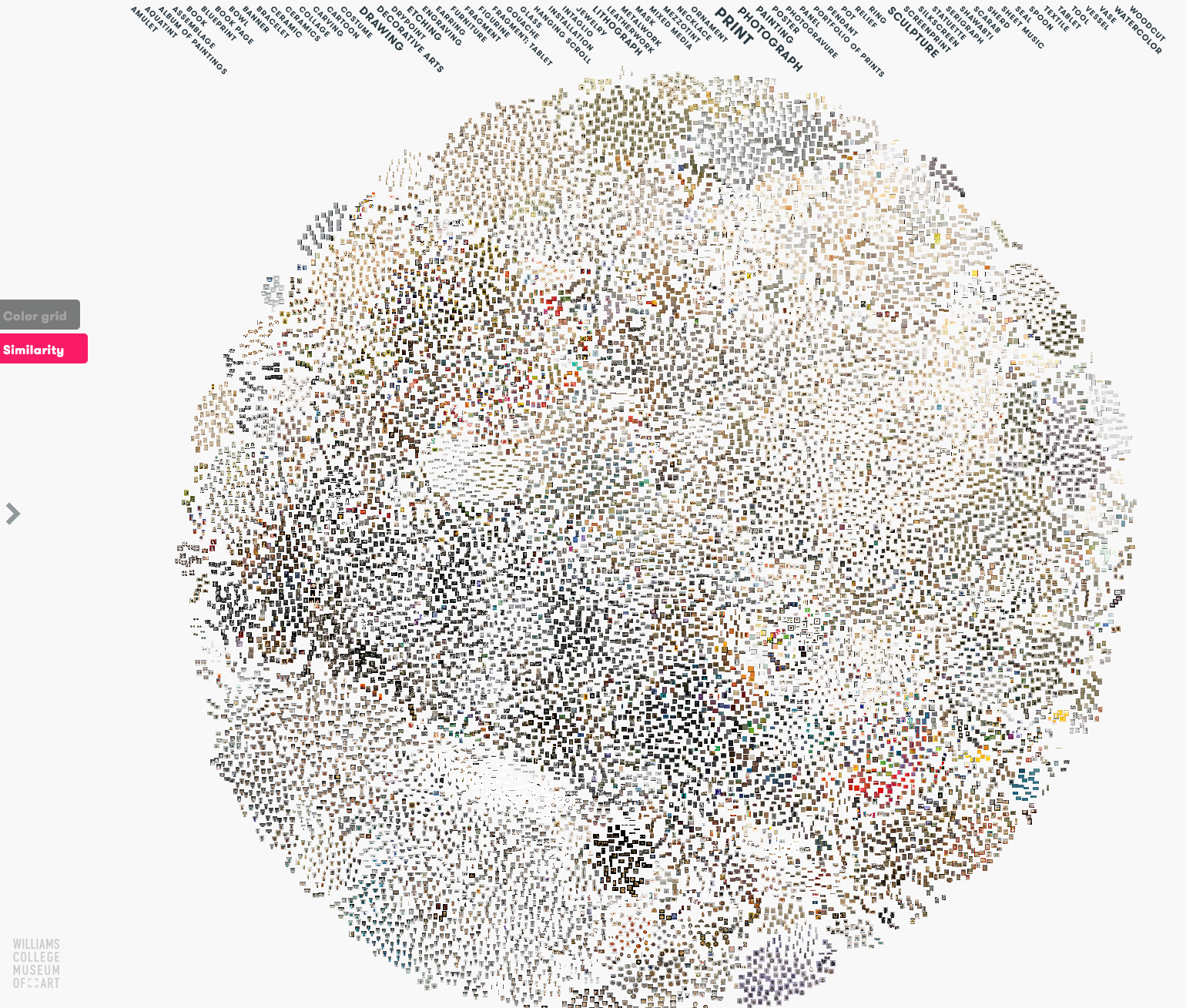

Current CNN-based CV models suffer from some (likely) inescapable forms of opacity. But one avoidable, yet pernicious form of opacity comes from discourses in computer-vision-for-beginners explainers, or implicit messages in simple and accessible visual search interfaces: that CV models are universalizing and can provide one true form of visual interpretation and clustering. But all-in-one collections viewers like WCMA’s collection explorer or reverse-image search interfaces like CMoA’s ArtLensAI provide a one-size-fits all notion of computer vision to their publics.

A screenshot of WCMA’s collections explorer visualizing photographed items in their collection arranged according to one approach of calculating visual similarity

Anyone who has dipped their toes into applying CV knows this isn’t the case - every model is wholly contingent on its training data and architecture. Just as there are many ways to photograph a work of art, so too are there many ways to construct a CV model. Presenting these models and their representations of images as digital surrogates can certainly help art historians better understand that these are tools like any technology for two-dimensional representations; simplifying, while simultaneously providing new opportunities for manipulation and analysis.

Yet while a photographer’s choices in capturing images of a given work are technically independent of other artworks they are photographing, a trained model is derived from the defined collection fo images that were used to construct it. Any multidimensional image vector you calculate from a CV model for use in, say, a visual search engine, is directly tied to that larger context, dependent on every artwork and classification in the original training set. This may be where CV models run up against the boundaries of our current digital surrogate discourses and solutions. Features like color profiles and embedded metadata for digital image surrogates can be reasonably standardized across institutions. It is impossible (at least under current CV architectures) to imagine one model that functions across the full wealth of our global artistic heritage. Object-recognition models derived from modern color photography, like InceptionV3, may discriminate fairly well between a portrait and a still-life paining. But they tend to shove all near-monochrome works on paper, like prints and drawings, into a relatively undifferentiated region of feature space. Moreover, models specialized to do object recognition may provide significantly different clustering results than those for pose detection, overall compositional patterning clustering, and so forth. With the works of art used for a training set as one axis (perhaps selected based on medium and technique, or by some kind of stylistic topology), and the guiding classification or clustering task as a second, we are left with hundreds of combinations of models that would be needed to create a nuanced visual search engine that could cover a wide gamut of multiple art museum collections and different kinds of user inquiries.

Rather than a “standard” art historical CV model from which everyone produces feature vectors, what we likely need is a research & collections information architecture that can accommodate a blossoming community of re-usable CV models, each with cogent guidelines on strengths, weaknesses, and appropriate contexts for use, alongside the customary technical details and training data contexts. As with much cultural heritage infrastructure, the challenges are as much about computing problems as they are about establishing shared conventions and a community of shared practices. More of our CV experiments in art history or other visual cultural heritage should concretely outline common operational needs and use patterns (as we attempted to do with our CAMPI whitepaper) beyond the context of that one specific experiment and collection. Approaching CV models and derivatives as digital surrogates that need the same kind of long-term management and useability considerations as our digital image management systems be an important step in building that eventual infrastructure.