SPARQL for humanists

As I noted in my previous post, image rights are a perennial challenge for all scholars, and art historians in particular.

I’ve been following the Getty/George Mason summer institute “Rebuidling the Portfolio: DH for Art Historians” on Twitter at #doingdah14, where the participants spent some time exploring the intersecting problems of image copyright and online image search.

One growing resource for images is Europeana, an aggregation service that is slowly working to build a massive database encompassing the holdings of Europe’s many “memory institutions”. Europeana conveniently allows you to filter your searches by copyright status. If I search for images with the term “landscape”, the left sidebar allows me to further refine by specific copyright status, and by the more overarching categories of “Can I use it?”

If you are searching Europeana for individual images, going through this visual interface is the easiest way. However, what if I want to see how copyright status breaks down by contributing institution, or by medium, or by date of creation? For this kind of query, we can’t just look at a list of results. We need to aggregate them.

This is where SPARQL comes in.

Europeana is rolling out their datasets as Linked Open Data (or LOD), a graph database format accessible via the SPARQL query language. I’ll leave it to Europeana to explain why they (and many, many others) are doing this. What I want to do is quickly dive in to show off what SPARQL queries allow us to do that we can’t do via the visual user interface.

Unfortunately, many tutorials on SPARQL use extremely simplified data models that don’t resemble the datasets you’ll find in Europeana or other institutions like the British Museum. This tutorial tries to give a crash course on SPARQL using a dataset that a humanist might actually find in the wilds of the Internet.

Contents

LOD in brief

LOD represents information in a series of three-part “statements” like this:

<subject> <predicate> <object> .

(Note that just like any good sentence, they each have a period at the end.)

Each subject, predicate, and object, is a node in a vast network. To keep these statements machine-readable and standardized, they usually come in the form of URIs, a.k.a. web links (I made up the first URL for the sake of argument, so don’t try following it!):

<http://data.rijksmuseum.nl/item/8909812347> <http://purl.org/dc/terms/creator> <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Rembrandt> .

Conceptually, what this statement is saying is this:

<The Nightwatch> <was created by> <Rembrandt van Rijn> .

It’s important to remember that each URI in the first statement links to many other statements. In order to get the “labels” for each of these URI’s, what we’re really doing is just retrieving more LOD statements:

<http://data.rijksmuseum.nl/item/8909812347> <http://purl.org/dc/terms/title> "The Nightwatch" .

<http://purl.org/dc/terms/creator> <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#label> "created by" .

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Rembrandt> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name> "Rembrandt van Rijn" .

The objects of these statements are just strings of text, known as literals in LOD terms.

They don’t link to anything else.

See the predicates in these statements, with domain names like purl.org, w3.org, and xmlns.com?

These are some of the many providers of ontologies that help standardize the way we describe relationships between data points, like “title”, “label”, “creator”, or “name”.

The more LOD that you work with, the more of these providers you’ll find.

Searching Europeana LOD with SPARQL

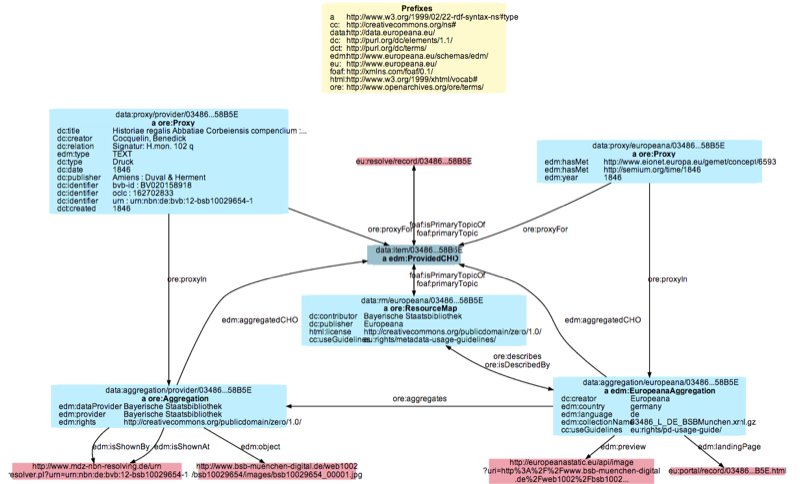

SPARQL lets us translate LOD’s heavily interlinked, graph data into normalized, tabular data like the kind you can open up in Excel, with rows and columns. Let’s say I want to get a list of Europeana images, with their titles and creators. Our first step is understanding how the data model works. Like many cultural LOD providers, Europeana has a… complex data model. I don’t want to paper over this complexity, so please bear with the following. In learning how to deal with these tricky models, you’ll come to understand just how much of the legwork SPARQL can do for you.

Figure out the model

We will be typing our query into Europeana’s SPARQL endpoint, so open that link in a separate window, along with the full version of the data model map below.

This is the data model for a single object.

Our first stop is the yellow box of “Prefixes”. These are shortcuts that allow us to skip typing out entire long URIs.

For example, remember that predicate for retrieving the title of the Nightwatch, <http://purl.org/dc/terms/title>?

With these prefixes, we just need to type dct:title whenever we need to use a purl.org predicate.

dct: stands in for http://purl.org/dc/terms/, and title just gets pasted onto the end of this link.

We’ll be using these prefixes for our query:

PREFIX dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/>

PREFIX edm: <http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/>

PREFIX ore: <http://www.openarchives.org/ore/terms>

Next, look to the center of the model, in dark blue.

That represents the primary link for this object, with all other information resources branching out from it.

The boldface label edm:ProvidedCHO is the identifier for this node.

Next, we need to figure out how to navigate from that link to the variables we’re interested in. Europeana splits its information among several subgroups for provider aggregations, Europeana aggregations, provider proxies, and Europeana proxies. You can read more about the distinctions between these, but in short:

- Proxies are metadata about the object itself. Provider proxies contain object metadata direct from providers, while Europeana proxies have additional generated metadata, such as links to geographic, bibliographic, and content databases.

- Aggregations are meta-metadata about the provenance, rights, and creation of these metadata. Like proxies, each object has a provider aggregation and a Europeana aggregation.

Let’s consider our target information and where to find it:

- Objects with a title

- And a creator

- And they should be images

In the upper-left corner of the model visualization you’ll see the box for ore:Proxy.

This is the provider proxy, and it contains info about the title, creator, and type of the object.

This box represents a bunch of LOD statements with that particular proxy as the subject, the various dc:XXX labels as predicates, and the values as objects.

More on this in a second.

Our first query

Back to the SPARQL query box, we can add in this:

SELECT ?item ?title ?creator

WHERE {

# we'll fill this in next

}

The ? items after SELECT are the names of our variables.

You can name these anything you wish; you will actually define what statements they correspond to within the WHERE {} section.

Below you’ll find the full query written out, with explanations for each line. You can cut and paste this directly into the Europeana SPARQL endpoint to see the results.

PREFIX dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/>

PREFIX edm: <http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/>

PREFIX ore: <http://www.openarchives.org/ore/terms/>

SELECT ?link ?title ?creator

WHERE {

# In the WHERE statement, we define the variables

# we asked for in the SELECT statement, as well as any

# intermediate variables needed to define those variables.

?objectInfo dc:title ?title .

?objectInfo dc:creator ?creator .

# These statements ask for ANY record that has the

# predicates dc:title and dc:creator. Because we only

# included the ?title and ?creator variables in our SELECT

# statement, the ?objectInfo variable will not show up

# in our results. But, we can still use this "throwaway"

# variable to shape the rest of our query.

# We only want objects of the type "IMAGE". This statement

# effectively restricts the output of every other statement

# in our query. Thus, we'll only get ?titles and ?creators

# attached to objects that are also images.

?objectInfo edm:type "IMAGE" .

# Finally, we want to get the canonical Europeana link to the

# object. Check the model map and you'll see the name of the

# predicate (ore:proxyFor) we need to use in order to retrieve

# that dark blue link

?objectInfo ore:proxyFor ?link .

}

The resulting table will give you every combination of link, title, and creator for “IMAGE” objects in the database. Note that objects with multiple creators, or multiple titles, will get multiple lines.

Adding more limits

What if we want to restrict this even more, by only retrieving completely public-domain images? We need to add a few more statements to our query, looping in the provider aggregation data section that contains the rights statement:

PREFIX dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/>

PREFIX edm: <http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/>

PREFIX ore: <http://www.openarchives.org/ore/terms/>

SELECT ?link ?title ?creator

WHERE {

?objectInfo dc:title ?title .

?objectInfo dc:creator ?creator .

?objectInfo edm:type "IMAGE" .

?objectInfo ore:proxyFor ?link .

# ^ these lines are the same as our first query ^

# Check the map again. We need to find the link from the

# provider proxy to the provider aggregation, which is in

# the lower left corner of the map. We'll create another

# "throwaway" variable called ?objectAgg. Like ?objectInfo,

# this link won't show up in our results, but it will let

# us restrict what the database returns to us.

?objectInfo ore:proxyIn ?objectAgg .

?objectAgg edm:rights <http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/> .

# Remember to surround any URIs with < and >, and always add

# a period at the end of every statement!

}

Try restricting these results even more — say, by provider, or date.

Aggregating with SPARQL

So far we have just been emulating the kinds of queries that you can make using the visual user interface. But what about aggregating these data?

One question is the distribution of rights: how many objects are totally open source?

How many have some restrictions?

How many are paid-access only?

So far we have just used SPARQL’s PREFIX, SELECT, and WHERE commands.

For this aggregation query, we will introduce COUNT, GROUP BY, and ORDER BY.

Locate rights information

First, let’s figure out how to access the names of the data providers and the rights statements for each object.

# Don't forget your prefixes

PREFIX dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/>

PREFIX edm: <http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/>

PREFIX ore: <http://www.openarchives.org/ore/terms/>

SELECT ?edmrights ?provider

WHERE {

# Rights and provider names show up in the provider aggregation

# section.

?objectAgg edm:provider ?provider .

?objectAgg edm:rights ?edmrights .

# Remember, we still want to restrict our results to

# images only, which means we need to link in the provider

# proxy section. Note that predicates only work one way,

# so we need to define ?objectInfo as the subject of the

# statement, then ore:proxyIn as the predicate, and our

# ?objectAgg variable as the object. SPARQL doesn't mind!

?objectInfo ore:proxyIn ?objectAgg .

?objectInfo edm:type "IMAGE" .

}

This gives us a row for every single image object with a provider and rights field. What we want to do is count them up. This is where our new commands come in.

Aggregating by variable

PREFIX dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/>

PREFIX edm: <http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/>

PREFIX ore: <http://www.openarchives.org/ore/terms/>

# We need to declare a new variable in our SELECT command.

# Because this is a calculated variable, it has a special notation.

# We need to tell it which variable to count (* means

# count all of them) and then what to name the new variable.

SELECT ?edmrights ?provider (COUNT(*) as ?count)

WHERE {

?objectAgg edm:provider ?provider .

?objectAgg edm:rights ?edmrights .

?objectInfo ore:proxyIn ?objectAgg .

?objectInfo edm:type "IMAGE" .

}

# Now we need to tell the database to count up every combination of

# ?edmrights and ?provider

GROUP BY ?edmrights ?provider

# And then we have an option of how to sort the results. Let's

# sort it by count, from highest to lowest, using DESC(). If

# we just wrote ORDER BY ?count, it would sort from lowest to

# highest

ORDER BY DESC(?count)

You will notice that running this command will take longer than commands that aren’t aggregating and counting. We are asking the database not only to retrieve, but also to match, count, and sort, so this may take a few minutes before your browser gets a response. Try grouping and sorting the rights statements by other variables, say, by providing country (in the Europeana aggregation subsection of the data model), or by year (in the Europeana proxy subsection).

Further reading

In this tutorial we got a look at the structure of LOD as well as a real-life example of how to write a SPARQL query for Europeana’s database. You also learned how to use aggregation commands in SPARQL to count results rather than just list them.

There are even more ways to modify these queries, such as introducing OR statements, or doing other mathematical operations more complex than counting. For a more complete rundown of the commands available in SPARQL, see these links: