Organizational Archaeology: Auditing a Library’s Digital Services

Starting last year, I’ve tried to write up posts like this after we launch new projects that have a public-facing component, whether it’s something like the NGA hack-a-thon, a new searchable database like The Index for Digital Humanities or a whitepaper like CAMPI. This fall, however, I spent much of my time on a completely internal project: a high-level audit of CMU Libraries’ digital infrastructure, from the servers we run on campus to the cloud services we use for all kinds of data storage. Unlike our public projects, I’m not sharing the 62-page report that Scott Weingart and I compiled, since we wrote it in a frank manner for an internal audience (and it would not make a lot of sense to an audience out of our specific context, anyway.) But like our public projects, I hope to talk here about some of the process behind the work.

Due to some intense reorganization in our library over the past few months, there was no one else in our org well-placed (and with the capacity) to take on a full inventory of our collections and operations systems. I have been gradually shifting my focus towards collections data infrastructure anyway, with the CAMPI project being an exciting example, so I was eager to take the job on. This was going to be a big departure from the coding side of my job that has dominated my first two years here. But an important aspect of the work of being a research software engineer / DH developer is consultative: auditing the state of a research project to understand where a data/computational intervention will make sense, and how to prioritize that work before digging in to implement anything. This audit was a chance to exercise those muscles in a specialized and extended way.

Easily the most delightful part of the process was taking a month and a half to interview more than 25 different coworkers across the libraries as “stakeholders” for their respective services - from our archival management system to our IR, to how we are using exhibition microsites like Omeka, to working through the finer points of oral history transcription and A/V preservation workflows. On the one hand, doing these interviews was a daunting proposition. Having been here only 2 years and change, I only had a superficial map of the terrain I was expected to be cataloguing in detail. On the other hand, this naïve perspective was uniquely enabling: having only been here for 2 years, I could ask a LOT of stupid basic questions!

- When was this system established? Who was in charge of it? Why was this software chosen?

- Walk me through the tasks you do with this system day to day?

- Who else uses this system? Do you keep internal documentation somewhere? How often is it updated?

- Are all of

$COLLECTION_NAMErepresented in this system? - How often do you need to go to IT for help with bugs? Tell me about a recent example?

- Are all of

$COLLECTION_NAMEREALLY represented in this system? - What is your plan for handing off this system to someone else if you change positions?

- Tell me about plans in the coming year to change the way you work with this system?

- THINK REALLY HARD, ARE THERE ANY ITEMS FROM

$COLLECTION_NAMETHAT AREN’T IN THIS SYSTEM? LIKE MAYBE THEY’RE IN A WORD DOC SOMEWHERE?

And, as a relative newbie, I suspect I was a somewhat more neutral face to talk to than a colleague who has worked with you on the same system for anywhere between five and twenty-five years, and who would carry all the baggage that comes with that. As one interviewee commented, “you should really hold these sessions with people reclining on a therapy couch!” That implies a far higher level of dysfunction than in reality! Truly, the conversations were a mix of therapy, of fact-finding, and of history lessons, too. And out of this laundry list of quotidian questions, which I purposefully carried out in wide-ranging one-on-one calls rather than via emailed forms, I could begin to build out a gradual portrait of things that are more difficult to ask about point blank - either because they are uncomfortable to discuss, or because one has become so used to the eccentricities of a system that it is hard to imagine how things could ever be otherwise. For example:

- What workflows have you been running for years, but which have always felt like square pegs in round holes?

- Which systems depend on each other, either directly (through APIs or data feeds), or indirectly (a human being needs to use them both to get a certain task accomplished)?

- Where are humans trudging through rote, repetitive workarounds because it was just too hard to get the software to work how you really needed it to?

- Where are the big problems that have always felt too scary to bring up with IT or administration, much less actually solve?

- What are your wildest dreams for what this system could do, forgetting, for a moment, how much work you think it might take to make happen?

Out of a long list of strengths and weaknesses, risks and opportunities, recommendations for new workflows and roles, and a hearty budget breakdown (double check that you’re still using the VMs you’re paying for every month, folks!) one of my favorite artifacts from this report was this:

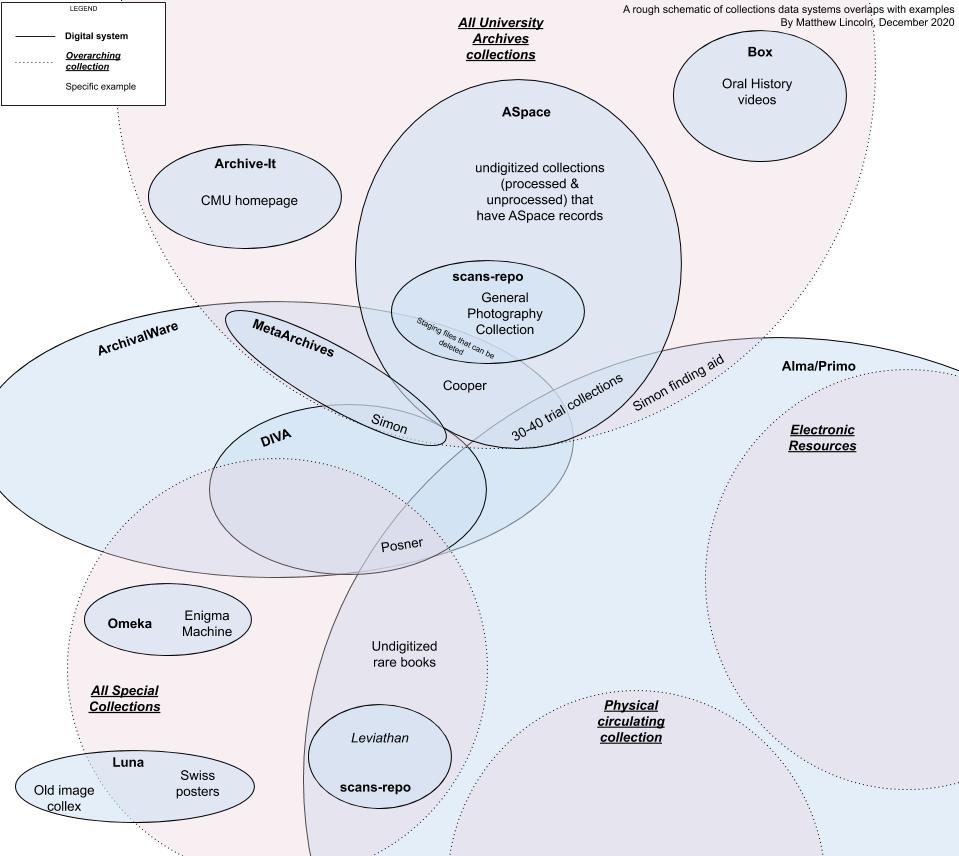

A Venn diagram of CMU’s different collections and the systems that hold representations of them as data.

It’s a very schematic-y Venn diagram that tries to outline how our major collection units - our University Archives, our Special Collections, and our commodity subscriptions & circulating collections - are represented across a patchwork of our ILS, archival CMS, multiple legacy DAMS, network drives, and experiments with cloud storage. One conclusion I will share publicly here (because I think it applies pretty much everywhere) is that no one person I interviewed could give me 100% of this picture. No one person could cleanly tell me where ALL the data for ALL the collections in our institution’s custody was truly stored. To paraphrase from our report, “we have a junk drawer of treasures, but no one has a complete index of where to find them all.”

But a great piece of news we could deliver alongside this sobering reality is that we have more personnel than ever who are excited to tackle these problems. Folks truly do want to sort out that junk drawer into appropriate bins (hopefully with happy, expressive APIs connecting them all!) I hope to post more on here in 2021 about the discrete steps we’ll need to take towards this Great Untangling, and how we’ll go about prioritizing which steps to take first.

In the meantime, I’m going in to our holiday break feeling a bit like the day after my doctoral comprehensive exams. The saying goes that after spending a semester reading hundreds of scholarly works in your field, you are the most well-informed you will ever be about your discipline. Each day after those exams, you’ll lose a bit more, and you’ll never again have the same amount of dedicated time to get completely up to date on the state of your field.

Indeed, this audit was going out of date the day we handed it in to our deans, as new updated invoices came in from our central computing center detailing the new VMs our IT staff were creating and destroying the midst of several parallel migrations. But I’m glad we were able to assemble this snapshot, no matter that it’s already slowly diverging from our IT reality. It makes the task of the Great Untangling graspable, tangible, and truly leaves me excited to get into the plumbing come January and start building new connections. And I’m happy to say those connections will not only be between our servers, but also between colleagues that I’d never spent much time with before this project, and now can’t wait to collaborate with.

May 2021 bring us all that same kind of positive change!