Sharing DH Code

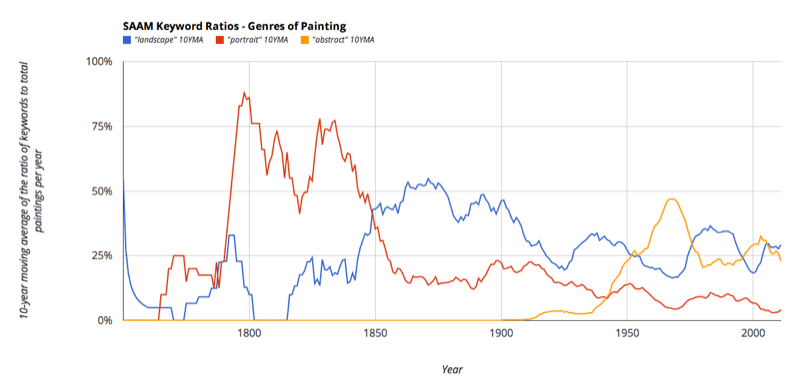

I have finally gotten around to releasing the code I used to generate my iconography network graph of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Some more charts of the trends in various keywords over time can be found here.

I had meant to push this out in time for the Archives of American Art symposium, but things got put on the back burner and when the symposium arrived, I realized I hadn’t put much of any commenting or documentation in the repository at all – neither in careful commenting in the source code, nor in a README file.

This is a no-no of course.

You really should be good about commenting as you code, especially for the benefit of future-you.

But it’s doubly vital when sharing your code with others.

There is a plethora of advice (even some advocating no comments at all!) available for documenting more conventional software projects that must remain legible to future developers and maintainers. Facilitating future development is, of course, fundamental to academic work: you want people to build their own scholarship off of your own – and cite it in the process! But an additional goal is also to make sure that someone may come along later and simply reproduce what you did, so that they might verify or refute claims supported by computational results.

As I finally got around to (at least partially) documenting the SAAM project code, I got curious if there are any other sources out there for best practices for uploading code made for digital humanities work – or any kind of academic project, for that matter. This question will only become more pressing as more and more journals are moving to GitHub or the like as code repositories, making the sharing of academic code a publishing norm.

A new article in PLoS Computational Biology on “Ten Simple Rules for Reproducible Computational Research” establishes several good precepts for documenting not only the code itself, but your process in developing and using the code on your datasets. Among the rules include documenting exactly how you reach every result, preferably doing so not just in a textual description but also recording it programmatically – that is, writing a small script (or Rakefile) that will run your scripts in the proper order and on the proper files, automating the reproduction process and essentially self-documenting your analytical process all at the same time. The authors also recommend you avoid manual manipulation of resulting data in favor of programmatic manipulation, in order to reduce the number of manual steps that one must correctly take in order to reproduce your results. (Lincoln Mullen has similarly suggested the need for programmatic data manipulation over at DHAnswers.)

Yet another consideration is how to document this code for audiences with diverse technical literacies. As I began thinking about it when I first published my si-scrape tool, does this code need to be made at least partially intelligible to the most technically uninitiated of humanities faculty? Or can/should there be some baseline expectation that you document the conceptual structure of your code for, say, a peer-review panel, even if you don’t need to get into the most granular levels of implementation (it strikes me that anyone interested in that level of detail would be literate enough to simply read the code.)

If you know of any other resources on best practices for sharing academic data/code, please let me know in the comments!